This blog post presents an overview of a brief experiment about synthetic data for agriculture. It is an end-to-end project; meaning that it will cover the creation of data to the results of a model which uses said data. This is a burgeoning field which has had enormous impacts in industries beside agriculture. I will briefly outline what this field is all about before going into the details.

I. Overview of the Problem

i. MACHINE LEARNING

Machine Learning is pattern recognition. These patterns can be purchasing habits, peak traffic prediction, or signs of disease in a patient’s X-ray scans. Once models are trained , they can approximate what an expert may say. Imagine a world with 100 experts in an important subject which is in such high demand that the number of requests for the experts’ opinion could never be met. If these 100 experts labeled data, a model could approximate their analysis enabling the entire world to benefit from their expertise.

However, in the present day, successful Machine Learning models rely on vast amounts of data. In more complex scenarios, like the medical setting, patient records/X-ray scans must be labeled by a human. Simply put, there is not enough of this medical data to have as significant an impact as Amazon performing product recommendations. That is the bottleneck to improving the quality of life globally with these tools.

This is the problem that Synthetic Data seeks to improve.

ii. Computer Vision

Imagine creating a model to count the number of apples in an orchard. This model will inform the growers of the progress of their crop, allow them to plan expensive labor, and monitor potential diseases or stresses they may need to manage. Ideally, this model would scan their orchard each day providing counts of apples. This could potentially lead to cost saving measures to make their business more profitable.

Images of the orchard are acquired daily for 1 year. Then a human looks at a fraction of these images and labels where the apples are in each image. These images are now “annotated images”. The annotated images are used to train a model. This in short, is how Machine Learning models are trained.

However, there are major problems 1) NUMBER ANNOTATED IMAGES : It would be a huge cost to pay people to click through each of these images. 2) BIAS IN AVAILABLE IMAGES : e.g. The weather from this year was generally sunny, there were very few cloudy days.

Ignoring these problems and creating a model from the available, single year’s images will result in a model that works very well, only some of the time; when the conditions were very similar to the year the images were acquired. Maybe the following year there were more cloudy days or greater humidity, both of which affect how the plant looks and grows, or changes the quality of the images. This breaks the model’s performance, meaning it can not be used for the cost-saving measures as desired.

iii. Synthetic Data

Synthetic Data is the crossroads between 3D modeling (used in videogames and TV/movies) and Machine Learning. Thanks to “Procedural Generation” we can create an infinite number of unique 3D objects. In the context of an orchard, you can imagine growing a seed into a tree which in turn grows apples. The “procedural” part means that this tree grows according to rules which have subtelties. You can now grow an ENTIRE orchard of UNIQUE trees with UNIQUE apples! It is as if you grew years of orchards in real life; every tree is different. This is in essence what synthetic data is; with one additional feature. This feature is “automatic annotations”. Since a computer program was used to grow these unique trees, the program also knows which pixel belongs to the tree’s trunk, leaves, or individual apples. This is incredibly intriguing for training machine learning models. Because not only do we have variable data, it is completely annotated. This saves humans the troubles of capturing and labeling images. Not to mention planting apple seeds then tending an orchard for years!

NUMBER OF ANNOTATED IMAGES : Now with our synthetic orchards, we can generate thousands, or even millions of trees to train our model with the push of a button.

BIAS: On top of this, we can also simulate tornadoes, hurricanes, fires, clouds, air pollution, and every possible type of stress (from insect damage, to hail damage, to heat stress, to frost). We can now address the issue of bias we would have from only acquiring 1 years worth of images from a single orchard. With enough knowledge about plant physiology, we can make the leaves bend, curl, or discolor in order to mimic real life conditions. In theory, this will make the apple counting model much more reliable and we can base our management decisions from the model with greater confidence ; reducing our risk and maximizing our profits.

II. Real Application

Creating the 3D models and Annotations

Arabidopsis is the “model” organism of plant biology, typically all innovation begins with the model organisms of science. We will continue this tradition with our explorations of synthetic data for machine learning and computer vision.

We start simple; we want to track the growth of arabidopsis plants. This means counting the number of leaves, and recording the size of each leaf. This tells us how well the plant is growing. Some arabidopsis plants may grow faster/slower depending on the conditions and their genetics. Our model will track this, taking a measurement (potentially) every minute/second/hour/day.

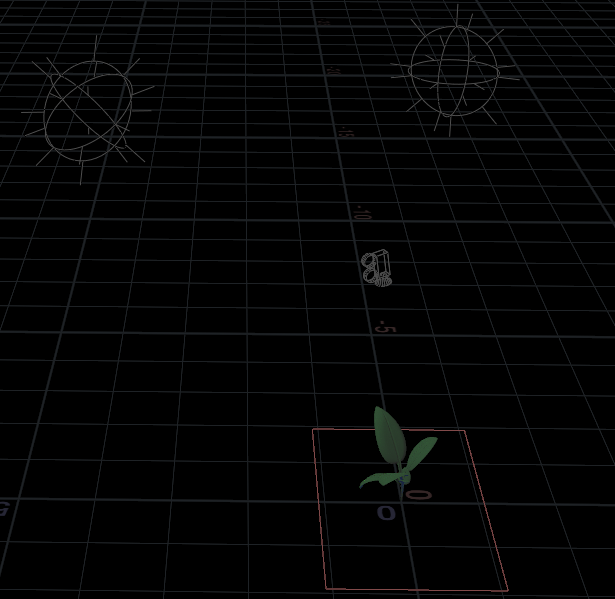

Introducing SideFX’s Houdini; You have definitely witnessed the the output from this software program if you’ve watched major movies or tv series in the past decade. This program is ideal for creating synthetic data because its foundation is set in the proceduralism which helps us produce unique plants with the click of a button.

With this setup in Houdini, we can create many unique plants and we know which pixel belongs to each individual leaf. The image below is how the arabidopsis model is represented in Houdini. Each node defines a feature of the plant and has parameters which affect the resulting trait. Another node in Houdini is responsible for generating many of these with random features which introduces the noise…

The result, as expected, are images of 3D models from above. Here are examples from a batch of plants. Additionally, we generate the pixel-by-pixel annotations; each pair of images corresponds to a 3D plant. Each unique color per image likewise corresponds to a particular leaf. Together, this is the minimum data required to train our Machine Learning model.

Next, we position some lights and the camera which controls the perspective of the synthetic images. Note: the spheres with lines coming out represent the lighting, we can control the intensity, color, direction, position, and number of lights along with the camera. This is of great significance and lends power to synthetic data (capturing many angles/lighting conditions can provide a greater number and variety of data).

To make the Synthetic images more real, we paste a picture of a pot and soil underneath the 3D plant.

The images are generated in pairs again and are processed in preperation for training the Machine Learning model.

The Machine Learning Model

In this experiment, ~200 unique plants/images were created. The numbers of leaves varied from 2-8 as defined by the Houdini nodes. It took approximately ~60 minutes to generate all of these 3D models and their images.

Once the data was generated, a Machine Learning pipeline was employed with the following tools: Docker, JupyterLab, and Keras/Tensorflow. The Machine Learning model was pulled from Matterport’s Mask-RCNN model with a pre-trained ResNet50 backbone. Then using only this synthetic data, the model’s weights were updated to learn the shape of arabidopsis leaves.

This model was then run over real images of arabidopsis plants. Recall, that this machine learning model had never seen a real plant before, as it was only updated on our synthetic plants created in Houdini. In this example, you can see it is able to find leafs with some degree of correctness! All without direct human intervention of manually labeling real images.

Discussion

Ask any Machine Learning Engineers what their greatest constraint is… if they’re performing the most common type of Machine Learning (Supervised Learning), they will tell you it is the lack of annotated data. To get the volumes of data they desire, their options are to pay local employees an expensive wage, outsource the work overseas, purchase the data from vendors, scrape data from the internet (if it is even available), or develop a complex scheme to get their users to annotate for them. Or they can employ synthetic data as we have done here with success.

This was a pilot study demonstrating the workflow. There is much much to be done with this arabidopsis pipeline. Apart from cranking out 1000’s of 3D models versus the 200 here, the 3D model can be improved. The textures can be improved, lighting can be made more realistic, finer details such as trichomes or diseases could be added to the leaves.

This experiment demonstrates the wide skillsets required to make machine learning successful: Domain-Expertise in the form of plant physiology, 3D modeling, Machine Learning Development, and general computational skills. Synthetic Data will undoubtedly be a core tool in the expansion of Machine Learning in agriculture as we extend valuable models to diverse crops and conditions. There are many more very interesting applications which I will highlight in future blog posts; for example, how can we use these procedural models to properly apply CRISPR to staple crops.

Bonus

An example of synthetic data for a rooting phenotype experiment simulating point cloud / LIDAR data. Given that we procedurally generated the roots in Houdini, we know the individual root hair each point originates from.

An early cut from my experiments with Houdini to create procedural plants.