This article highlights 3 recent papers involved in generating massive datasets and training machine learning models on them. Insights into promoter design and ML tools follow.

Promoter Engineering: Survey of 3 papers

Deciphering eukaryotic gene-regulatory logic with 100 million random promoters (2020)

doi:10.1038/s41587-019-0315-8

Model-driven generation of artificial yeast promoters (2020)

doit:10.1038/s41467-020-15977-4 —

Synthetic promoter designs enabled by a comprehensive analysis of plant core promoters (2021)

doi: 10.1038/s41477-021-00932-y —

Background

Synthetic biology is gradually adopting more machine learning models; Models akin to the algorithms which are driving the FAANG companies and startups across every major industry. In the context of biology, these models will enable tweaking biological pathways, genes, and proteins to produce value in the form of biomolecules, from fuels and food to potentially novel pharamaceuticals.

However, the biggest barrier to adoption of data-driven models is the lack of relevant data; a requirement to train machine learning models. There are many diverse tasks these models can assist engineers with. As the field of synthetic biology continues to mature the possibilities will compound upon eachother. One of the most practical starting points for creating these models is at the beginning of the central dogma of biology; the gene.

The Gene

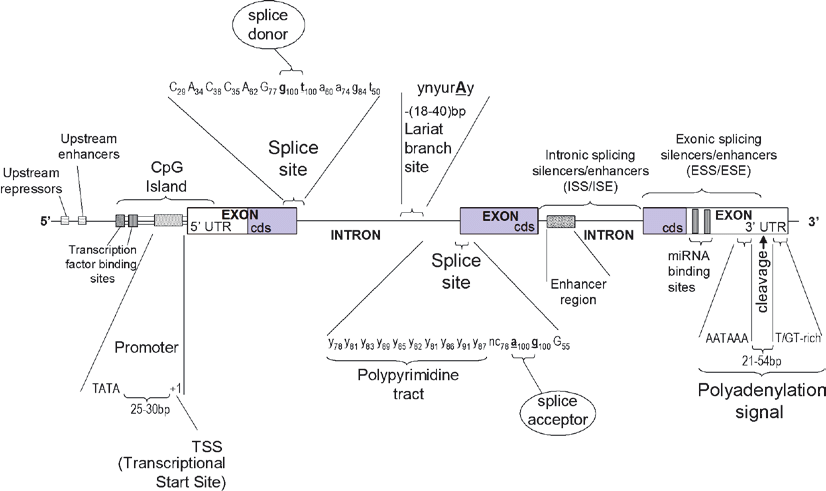

The anatomy of a gene is deceivingly complex; its definition is mostly a philosophical one. In the early days of biology, in the first half of the 20th century, it was limited to the central dogma: a gene is DNA which gets transcribed to RNA which gets translated to Protein. Today, this definition of a gene does not hold up. Components of a gene includes but may not be limited to: The promoter, the Transcription Start Site (TSS), the 5’ and 3’ Untranslated Regions (UTR), exons, introns, enhancers, and silencers.

The anatomy of a single gene. Source:Barnes, Michael. (2010). Exploring the Landscape of the Genome. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.). 628. 21-38. 10.1007/978-1-60327-367-1_2.

The Promoter

Today, we will be discussing the design of gene promoters. They are truly the beginning of gene expression, which influences protein expression and thereby protein activity in a cell. The promoter functions as an attractor to RNA polymerase, a protein which initiates transcription of DNA to RNA. Every gene has a unique promoter sequence of base pairs (A,T,C,G) which influences how often RNA polymerase proteins find the correspeonding DNA for the gene. Additionally, promoters contain motifs or sequences which attract specific transcription factor proteins which may attract or block RNA polymerase proteins. Promoters may contain core promoter elements like the TATA box which greatly increases its expression strength and is commonly found throughout genomes across all life. By designing promoters, we can control how much RNA is produced.

The ML models

In short, we’d like to design a model which takes in a sequence representing the promoter (e.g. TTACCATATACGGGAGAGCGA) and get out the expression of the gene this promoter belongs to (e.g. 15 copies)…

Designing promoters for testing

Promoters are sequences upstream of the gene. They can be anywhere from approximately 100-1000 base pairs long. Given there are 4 base pairs (A,T,C,G) even considering the shortest promoter sequences of 100 base pairs, there are 4^100 or 10^60 possible promoter sequnces; an astronomically high number.The goal is to generate many promoter sequences to understand how they influence transcription. Today, we can quickly print out new genes and promoters given their sequence. We can generate many random variations to study their effects on gene transcription.

Massively Parallel Reporter Assays

Back to the original problem; How do we generate relevant data that allows us to train models to design a promoter? Molecular biology is always innovating, as much as any other field of research. Today, there exists massively parallel reporter assays (MPRA’s) which are able to generate massive amounts of data with extreme constraints; thereby allowing us to design experiments to collect relevant data.

These approaches generate millions of data points, which is what makes them so intruiging for training machine learning models. When there are quadrillions upon quadrillions of potential combinations of promoter sequeneces, the scale of datasets is crucial for making models which are exposed to enough sequences to recognize useful patterns.

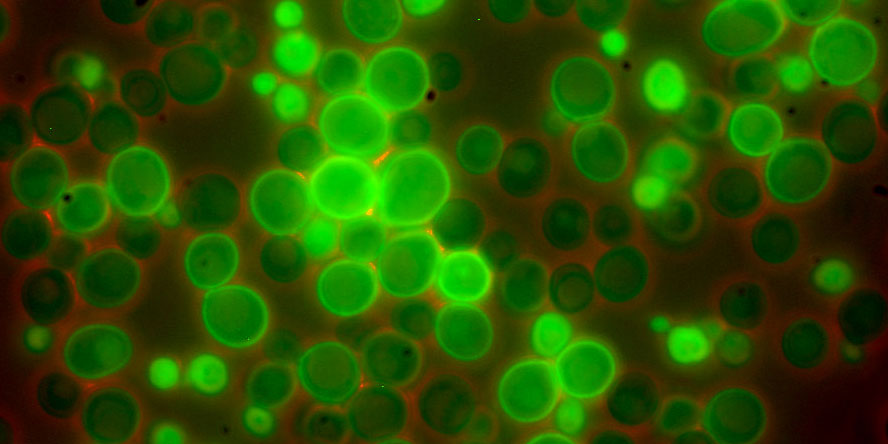

MPRA’s use cells which contain a given promoter-reporter gene. The reporter gene is typically GFP which emits a green light. The strength of the light corresponds to the strength of the promoter. In the 3 papers we look at today, they use each use one of the following tools.

1) FACS-seq : Fluorescent-Activated Cell Sorting

FACS-seq relies on individual cells being given a single promoter-reporter. Millions of cells at a time are sorted into bins based on the strength of the signal from the reporter gene. The cells are collected in these bins, then sequenced to retreive their unique promoter sequences. The data from the bins they are found in is the target for the training data for the models.

2) STARR-SEQ : Self-transcribing active regulatory region sequencing

Contrary to FACS-seq approaches, individual cells are given multiple promoter-reporters. The promoter strength is quantified by sequencing all RNA’s in a given cell.

Source: https://www.yeastgenome.org/ - Example of how yeast with different promoters (with different strengths) may appear

Designing Promoters

Once the experiment is performed, data collected, and ML models trained, you can now design promoters. For instance, if we wanted to increase the expression of a gene of interest, perhaps it is bottlenecking a pathway, we can use CRISPR to introduce SNP mutations in the natural promoter, without introducing a whole new version of the gene (which may be important for political regulations).

(e.g. go from ‘ATTTCATTT’ to ‘ATTTCGTTT’) via a CRISPR-induced mutation

There are two methods used by the mentioned papers.

1) Brute force Evolution: Since we have a model, we can take the native promoter and perform every base pair mutation (testing out potentially millions of possible results) to find the mutation that increases strength. This process can be repeated until a desired promoter strength is found.

2) Gradient Ascent: This approach leverages the machine learning model itself. Typically the models are trained with Gradient descent. Here were can figure out which mutations are most likely to increase the output(promoter strength).

Individual Papers

So far, we’ve covered a somewhat high level overview of what goes into designing promoter with machine learning models. There are lots of caveats and exceptions when you go further into the details, as is the nature of biology.

The following 3 papers are similar in that they produced massive datasets and machine learning models, in a way that I think is clever and efficient. They are, in my opinion, exceptional datasets, for kicking off synthetic biology with machine learning. Next, I will go into more specific details and my takeways for each of the papers.

Deciphering eukaryotic gene-regulatory logic with 100 million random promoters (2020)

This paper generated by far the most data of all 3 papers. The sequences were completly random. They developed a Gigantic Parallel Reporter Assay to assist in the scale of tested promoters.

- Their experiments yielded over 6 billion base pairs of data (this is about the same an entire human genome, but in this case just of promoter-reporter pairs)

- Transcription Factor motifs are abundant in random DNA at varying strengths

- 80 base pair regions were randomized between a known promoter scaffold

- These randomized promoters had up to a 50-fold difference in their strength

- Different contexts were tested ( yeast w/ randomized promoters grown in different mediums; different sugar levels which affects transcription factor protein levels)

- Few Transcription Factors had strong effects on promoter strength; rather there were many transcription factors with small effects

- Transcription factors interacted with eachother and nucleosomes present on the DNA to affect promoter strength.

- The location of a motif affected its contribution to promoter strength

- R2 of 0.843-0.904

</ul>

-------------

### Model-driven generation of artificial yeast promoters (2020)

This paper reports a MRPA performed in yeast. It pays particular attention to the sequence within a promoter between *known* motifs. These motifs are the TATA box, TSS, and several transcription binding sites. The contribution of these spacer sequences between motifs was modeled. Fewer promoters were generated relative to the previous paper but they were more specific and biased towards existing promoters.

- Approximately 1 million sequence-expressions profiles were generated between 2 experiments

- Utilizes FACS-seq to measure strength of each tested spacer sequence

- Created a CNN models to perform predictions

- R^2 of 0.79 to 0.84

- Directed evolution and Gradient Ascent were used to design new promoters

- The randomized promoter sequences uncovered the presence/effect of other transcription factor binding sites as found in Yeastract database

- AT/CG biases were discovered at different regions of the promoter effecting overall strength

</ul>

-------------

### Synthetic promoter designs enabled by a comprehensive analysis of plant core promoters (2021)

This paper is the most distinct of the 3 for several reasons: it is performed on plant promoters (not randomly generated ones), it surveys several species, and it uses STARR-Seq. The genomes of Tobacco, Maize, and Arabidopsis were scraped for genes, and annotated promoters were identified. Generalized promoters from this dataset were customized to test various hypothesis (like location of motifs). This is not as robust as the previous examples, but is still a clever way to generate data. It would be expected the models are not as capable of predicting the effects of single base pairs. It does yield valuable insights into the activity of promoters in the plant kingdom.

-------------

- Different species had different characteristics for promoter activity, e.g. tobacco promoters were moreso affected by GC content (low GC, higher activity)

- The TATA boxes had different locations depending on the species; location affected strength of effect

- TATA box presence provided a 4x stronger promoter; the location depended on the system

- Most (~2/3) Transcription Factor Binding Sites, did not significantly change the promoter strength; this depends on cell type / species

- The presence of Transcription Factors decreased the effect of enhancers (another component of genes which is not the primary topic of this post)

- Plants are affected by their own core promoter sequence, the Y patch, which is similar in effect to the TATA box.

- R^2 of 0.67-0.71, lower than the previous models, likely due to testing a wider array of species/tissues and not generating millions of randomized sequences.

- Training models that used data from all experiments (species/tissues) the predicted promoters were able to increase strength in all scenarioes </ul> ------------- #### Recap These papers report datasets and discoveries related to promoter design, one of the first steps in designing genes. Their power comes from the ability to generate large amounts of diverse promoters which are assayed to test theier strength. We can see that the accuracy of the models corresponds to amount of data generated. Although the promoter is one component of a gene it has many complexities to it including the presence/absence of transcription factors, core elements (like the TATA box), and effects of their locations within the promoter. Once we have models there are different approaches to use them to design novel promoters to produce target expression patterns. With plants, there are more factors to consider, namely the interaction of the promoter with other elements of the gene like enhancers and silencers. Additionally, promoter design for multi-cellular organisms like plants is highly cell-type specific, so even more data must be generated for them relative to yeast systems. The promoters optimize genes, but genes are only 1 part of the central dogma (DNA, RNA, Protein). There are still models which must likewise have massive datasets generated for RNA and Protein. While RNA is feasible at this scale due to the nature of nucleotide sequencing, proteins are much less managable with current protocols. For example, a single RNA strand may translate 1 protein or 100's of proteins, RNA's degrade at different rates (10's of seconds to minutes); the same goes for Proteins. Proteins can be optimized for their binding affinity or enzymatic activity. The list goes on for future models... These experiments were conducted a long time in the past by machine learning standards. They used CNN's or convolutional neural networks. Since then, other model architectures have become more prevalent, like transformers. These experiments can be reproduced with new models to potentially increase their effectiveness, and explainability, yielding more insights from the same datasets. In summary, generating data effectively *at scale* is key to the training and application of deep learning models. These three papers are excellent examples of this endeavor. Most of the code and data are publically available. To increase the adoption and commercialization of tools for synthetic biology, such studies should be funded and given priority.