This post covers a side-project which scrapes a database, finetunes a language model, and does an analysis on the results to predict amino acid residues with modifications.

I. Language Models

i. Language Models Background

Since 2017 the most popular deep learning architecture has been the transformer. Originally it was used in natural language processing for human languages. Typical applications were classifying snippets of text, making conversational chatbots, and more. Research into transformers has shown that they contiunally improve as they become larger with no end in site. This trend has not slowed down; in 2022 we may see the first trillion parameter models. Their novelty to problems lies in their attention mechanism. This allows the model to learn representations for words in a sentence that are unique to their context. A second novelty is the ability to leverage unsupervised learning. Before an actual application is trained in a supervised manner (e.g. with labels) the dataset undergoes a masked language modeling training session where random words are

From huggingface.co/large-language-models

From huggingface.co/large-language-models

ii. Protein Language Models

Relatively recently, around the beginning of 2020, these language models have been applied to protein datasets. In biology, it is common to hear the exclamation that we are sequencing more and more DNA and proteins each year at an exponential rate. This is true, but the primary outcome of all these seqeuencing studies is just that; sequences. Sequences of proteins we can be sure exist in nature. The majority of these seqences are not annotated, for example, with information about their functional sites, solubility, stability, etc… However, the transformer language models have shown that unlabled sequence (or text) data is enough to get a start once the dataset becomes large enough. This is naturally a good fit for all the sequence data that is now available. Several iterations of protein language models have been developed, that follow a similar suit to the ones trained for human language. However it is still relatively early in this niche of language models. It is likely we will see continual improvements in how these models are pre-trained and how their architectures are better suited for proteins (instead of human languages).

From Rives et al, Biological Structure and Function Emerge From Scaling Unsupervised Learning to 250 Million Protein Sequences, 2019. Here we can see that the language model learns properties of amino acids and groups them accordingly

From Rives et al, Biological Structure and Function Emerge From Scaling Unsupervised Learning to 250 Million Protein Sequences, 2019. Here we can see that the language model learns properties of amino acids and groups them accordingly

iii. HuggingFace

HuggingFace is an open-source framework that has captured the Natural Langauge Processing market. They’ve developed an API that allows users to quickly iterate on ideas while abstracting away much of the architecture and pre-processing tools. This allows users to focus on how they handle their data thereby allowing them to focus on ideas of how to best fine-tune existing models and evaluate them. They make the most popular architectures available as well as pre-trained models which usually are trained on massive datasets individuals or small companies would not be able to feasibly reproduce. This has allowed many companies across a wide range of sectors to leverage Natural Language Processing in their work to generate value by finetuning these models which is a major chore in itself.

Currently, they have several biology-based language models which are pretrained and available on their service. ProteinBERT has been made available and pre-trained on 100 million protein sequences and GO-ontologies (aka some proteins have labels). It provides a fine example for biologists interested in proteins to experiment with the standardized workflows available to other industries.

II. Post-Translational Modifications in Proteins

i. Post-Translation Modifications or PTM’s

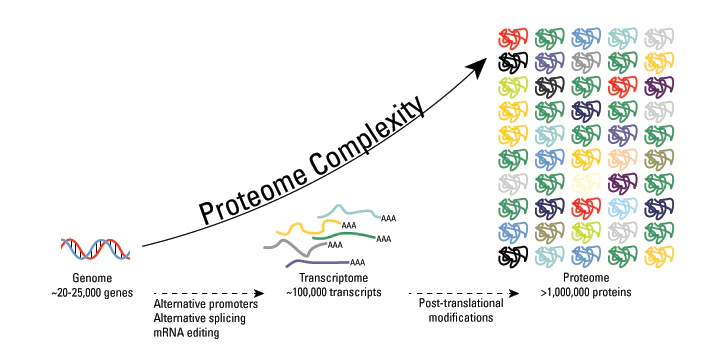

Protein biology is complex; especially in eukaryotes which possess post-translational modifications or PTM’s. A protein is composed of a string of amino acids which fold themself into complex 3-dimensional shapes. Some of these amino acids are known to have chemical modifications or PTMs. The presence of these changes the behavior of the protein: the subcellular localization, stability, functionality, and more. Therefore it is important to be aware of their presence and effects for proteins in pathways of interest otherwise your experiments may experience greater noise making it difficult to do predictions or optimizations.

From thermofisher.com . The space of possible proteins is huge when you factor in PTM permutations.

From thermofisher.com . The space of possible proteins is huge when you factor in PTM permutations.

ii. Yeast Amino Acid Modifications (YAAM) http://yaam.ifc.unam.mx/

It was previously mentioned that we are producing a lot of sequence data without annotations. This makes it difficult to find good datasets to use language models; as they require a lot of data compared to previous methods. Nonetheless there does exist some good sources of datasets to use. For example, in previous blog posts MPRA’s were discussed. The YAAM database presents another, albeit small, database that can be used to test these protein language models.

The database consists of approximately 80% of all known yeast proteins, those which contain known PTM’s. Essentially it is a set of sequences with labels of PTMs on individual amino acids. The PTMs are labeled on the canonical protein sequence. This means it’s the protein sequence of the reference genome which is what most yeast biology researchers use. In reality, these PTMs were found on variants of the reference sequence, however, this information is not preserved in the database. This would have been interesting information. Nonetheless, we are left with ~4800 protein sequences with labeled PTM’s.

Approximately 2% of the amino acids across all sequences are known to have PTM’s. This is an extremely imbalanced classification problem. Our dataset also being small makes this a very challenging problem to identify the two percent of amino acids with PTMs, however, this is the task at hand.

A single sequence with its PTM labels from the YAAM database

iii. NER (Named-Entity Recognition)

This is a common task in Natural Language Processing. Whereby a model takes a sentence of words (‘The man bought a newspaper from the New York Times’) and classifies, for example, all the nouns in the sentence. Or in this case [0 1(man) 0 0 1(newspaper) 0 0 1 (New York Times)]. This is the paradigm that will be followed for predicting the PTMs.

e.g. the model will take in a protein sequence [M P S L S T …] and output [0 0 1(S) 0 0 0 … ] Which designates the first S(serine) amino acid posesses a PTM.

III. Finetuning ProteinBERT

i. Testing Fine-tuned embeddings

Language models learn the ‘context vectors’ as mentioned earlier. Each amino acid will be assigned unique 1024 numbers which is its representation. The representation of the Serines in a single protein sequence will therefore be different. This is because during the pre-training, the patterns of surrounding amino acids is different and this is what transformers learn with masked language modeling. So the first question we will ask is if ProteinBERT has already that Serines with modifications have distinct representations than Serines with no modification. At the end of the day, this is our task.

We can see 50,000 serines from sequences in the dataset in the PCA plot below. As expected, they are not identical. Yet, the distributions of the modified versus unmodified Serines are not distinct. This is to be expected since the pre-training had no explicit knowledge of the presence of PTMs. In the next steps we will fine-tune the language model in order to seperate the modified from unmodified amino acids.

PCA of Serine embeddings; the model does not seperate them so it cannot classify them.

ii. Regression ; predicting total number of PTM’s given a sequence

We want to be able to seperate the representations of modified versus unmodified amino acids. To see if this is possible we will give simple labels to each sequence. In this example, the total number of annotated PTM’s are provided and nothing else. Surprisingly, this acheives our goal; the modified versus unmodified amino acids begin to seperate into distinct clusters. This model is trained without knowledge of exactly which amino acids are labeled as 1 (PTM-present) yet it learns to pay attention to Serines which are modified regardless.

After providing the sequences with labels via finetuning we can see it learns differences between modified and unmodified serines.

iii. NER - classification ; classifying 1/0 to each amino acid in a sequence

In this part, we will use the full labels of a sequence, e.g.

[ M S L P P T … ] and [ 0 0 1 0 0 0 …]

The model will be fine tuned with these labels for each amino acid. Hopefully it will be able to correctly classify the PTM amino acids as being 1. Deep Learning models are very greedy, in this case the dataset is extremely imbalanced, so the naive model will always predict the amino acids to have a 0 label since it will acheive an impressive 98% accuracy! But this is useless since we are interested in the 2% of amino acids labeled 1. We must take a trick from machine learning which is changing our loss function (which is used to inform the network how good it is at predicting) to the Cross-entropy loss. This loss gives us the ability to retreive the probabilities the labels are 0 or 1. So it may predict it is a 1 15% of the time. This would already be improved over the standard loss function. Additonally cross-entropy loss allows us to use label smoothing and class weights. These let decrease the confidence of the model always predicting the majority (98%) class and update the model with a greater degree when it incorrectly predicts the minority class as 0.

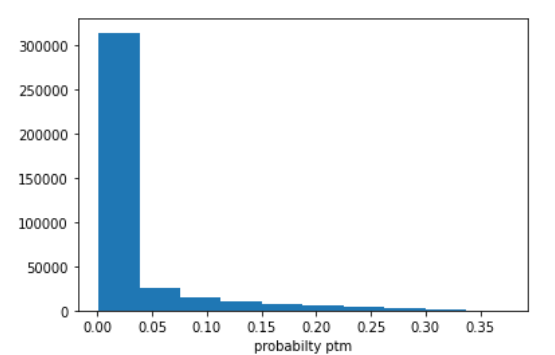

The loss combined with the NER labels allows us to push the predicted probabilties away from being 100% confident every amino acid is not modified. With this model, it never predicts any amino acid is modified (since it the predicted probability is always under 50%). However it is pushed in the right direction. We can look at the amino acids which are most likely to be modified and note that they are indeed modified.

The predicted probabilities for amino acids to be modified across the entire dataset; there is still improvement, but before fine tuning, the distribution was completely 0.00 for all amino acids.

IV. Recap

The present problem of PTM idenfication was extremely challenging due to the small dataset and imbalance. However, the model begins to learn which amino acids are modified. We introduced new parameters to the model to acheive this; label smoothing and class weights. We can improve the models performance considerably with hyper-parameter tuning. This method chooses different values for all the important machine learning parameters (e.g. learning rate, batch size, weight decay, label smoothing, etc…) to find the optimal values. With more time and compute this could be done. However, it takes hours to train one model to convergence alone. 100s of models may be trained in a setting where we would want to make this the best model possible. Other tricks that could be applied would be collecting more data. The ptmDB has ~2 million PTMs from sequences across many different organisms. This data could be used to fine tune the model before fine tuning a second time on yeast data , or our organism of interest. In the beginning it was mentioned that larger language models perform better, and this is actually an option with ProteinBERT/HuggingFace since a larger pretrained model is available. Both of these approaches would likely improve performance further, but take a lot more time to train.

This has been an early example of using protein language models for biological sequence prediction. This may be the first time this tool was applied to post-translational modifications. It is expected that we will see many more examples as the tools become more widespread and more iterations of the pre-trained language models are released by universiites and companies.