Using genetic algorithms to evolve genes…

Promoter Evolution : Genetic Algorithms

In this article we will use promoter data from one of the previously mentioned papers by Kotopka and Smolke. First, a CNN deep learning model will be trained on the data to predict each promoter’s expression levels. Then, a genetic algorithm will be written to mutate a promoter to an expression target level.

Genetic Algorithms

Genetic algorithms have nothing to do with genetics, instead they take inspiration from the process of evolution; mutations, breeding, and selection in order to optimize fitness.

In the context of machine learning and computer science, these genetic algorithms are developed in order to search parameter space of a model.

For the problem of promoter design, the search space consists of all possible inputs; or all the possible sequences. For a 100 base pair sequence, there are 4^100 or 1.6 x 10^60 combinations; an unfathomably large number. Instead of testing each combination by running it through the model which may take years or decades on even the fastest computers, it would be smarter to use a heuristic to select which sequences to try. If one sequence gives a result better than random sequences; the good sequence may be slightly modified to perhaps improve it further.

The algorithm consists of themes from biology: individuals, populations, mutations, meiosis, genetic drift, and more. Individuals represent single sequences

‘ACCCAGGG’

These individuals undergo mutations, selections, and mating.

A SNP mutation is a simple base pair change, or changing one of the nucleotide indentities

A->T ‘TCCCAGGG’

There are more mutations, for example inversions (flipping consectutive base pairs), deletions (removing base pairs comepletely) or additions(adding nucleotides in the sequence). Mutations ‘explore’ the search space around a sequence, or individual in a population.

The population is made of many individuals. Additionally, these individuals can mate; which involves mixing the individuals sequences with ‘crossing over’.

Crossing over swaps out streches of the sequences between two individuals. The effect of this is to increase the diversity of the population. This is where most diversity in nature comes from; different combinations of base pairs results in most variation, mutations make up a small portion of the phenotypic diversity.

Fitness is the measure of an indivdiual’s desirability. For promoters, we may wish to create a stronger promoter to increase gene expression. Additionally, we may want to limit the number of mutations from the original sequence. Both the gene expression strength and distance can be part of an individual’s calculated fitness. Each generation, there may be a cut-off for individuals to persist in the population. Those below a cut-off for a fitness score may be discarded.

This process of mutation, mating, and selection repeats until a good enough solution is found. This is analagous to evolution in biology and works well in this case to provide a heuristic solution.

Convolution Neural Networks

Convolution Neural Networks, or CNN’s are a class of deep learning model which has been popular for tasks related to vision and text. Today, CNN’s have been the most popular tool for genetics with deep learning, however, it is beginning to replaced by other algorithms. Nonetheless, it provides a good and quick baseline for comparing models.

CNN utilize convolutional layers which work by ‘learning’ filters which correspond to features in the input text. The filters, or kernels, are a set length. The filter then moves, one character a time down the text, like a sliding window. At each step, the kernel collects the feature of the text within its window which is saved in a new version, or representation of the text. In theory, these filters will learn relevants features which enable prediction of the target task.

These convolutions over the text are often paired with another operation; pooling. Pooling effectively shrinks the dimensions of the text, thereby reducing the size of their representation and bringing together features which are distant. Eventually, the filters learn useful operations which incorporate distantly related parts of the text which are relevant for their pattern and target.

In effect, CNN’s learn features and compile information across a seqence into a smaller, more condense representation. This representation can then be used for other parts of a deep learning algorithm. The most simple model that can use CNN representations is a series of linear layers; the backbone of most deep learning tools.

Training a baseline CNN

We will use data from the Kotokpa and Smolke study which generated tens of thousands of promoter-expression pairs. They studied two promoter systems containg transcription factor binding sites, ZEP17 and GEV4, where the promoter lengths were 272 and 312 base pairs respectively. The promoters were tested under various conditions. After filtering for the highest quality datapoints with detectable expression levels, about 160,000 pairs remained.

The data was preprocessed to accommodate the model. Raw sequences were converted to numeric values which were converted to one-hot encoding [1,0,0,0] , [0]

Raw : (‘ATTTAGGC’)

Numeric : (‘1,2,2,2,1,4,4,3’)

One-Hot : [1 0 0 0], [0 1 0 0], [ 0 1 0 0], [0 1 0 0 ], [1 0 0 0], [0 0 0 1], [ 0 0 0 1 ], [0 0 1 0]

With this input, the one-hot encoded sequences are passed to a convolutional layer with 10 channels; each channel correspeonds to a different kernel or sliding window. Each of these sliding windows may learn different features to assist in the task of predicting expression strength. These 10 new representations of the input text are then pooled; the text is split into chunks of 2, the higher value is kept and the other discarded. This condenses the sequence making it shorter; which would enable future convolutional layers to learn spatial features. With these new representations, the numeric values of features of the text are flattened out into a list of values which is finally passed to linear layers to predict the final value.

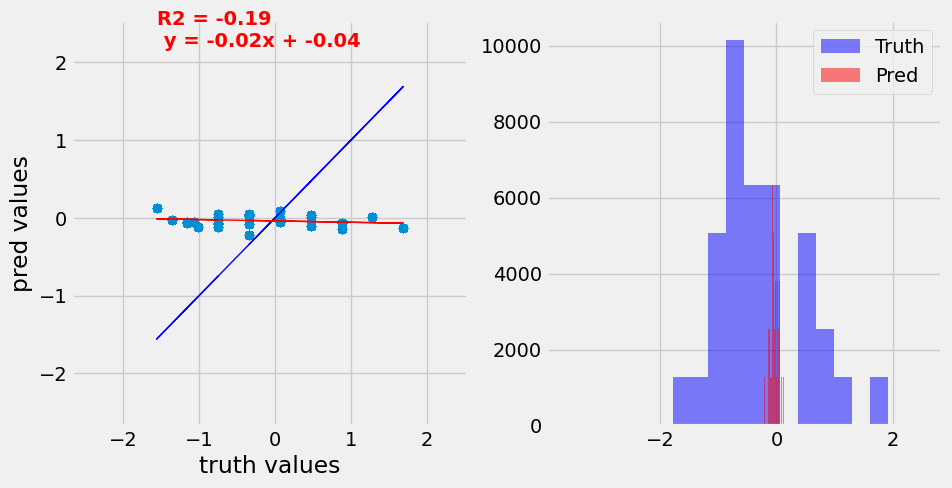

The trained model is the most basic CNN; however it does a very good job at predicting expression values all things considered. The result is a model which can take any DNA sequence (under 313 base pairs) and predict its expression in yeast.

Predictions on the validation set before and after training demonstrating the ability of the CNN model to predict accurate expression values for the input promoters.

Developing a baseline Genetic Algorithm

This genetic algorithm is as simple as the CNN. It is more analogous to vegetative propagation or inbreeding plants. For example, bananas and other horticulural variaties are improved through mutation breeding without meiosis or crossing over.

In this genetic algorithm, we start with an initial promoter sequence and put it through our model to get its predicted strength. Then we decide that we have a target expression level we would like to reach. This will be our target for evolution.

First 200 individuals will be generated using our input sequence as the seed. Each of the 200 individuals will receive 1 random SNP mutation. These new sequences will be run through the CNN model to get an expression score. These scores will be compared to the target value to determine each of the new sequences’ (or indviduals) fitness. The top 50 individuals will get to undergo the next generation and perform mitosis; or clone themselves. so these 50 individuals will clone themselves and represent 150 of the 200 individuals in the next generations population. The remaining 50 will be randomly generated in the same fashion as the original 200. This process will be repeated for 50 generations; we could also set a stop condition (like when it reaches within 5% of the target value to top evolution and return the most fit sequence).

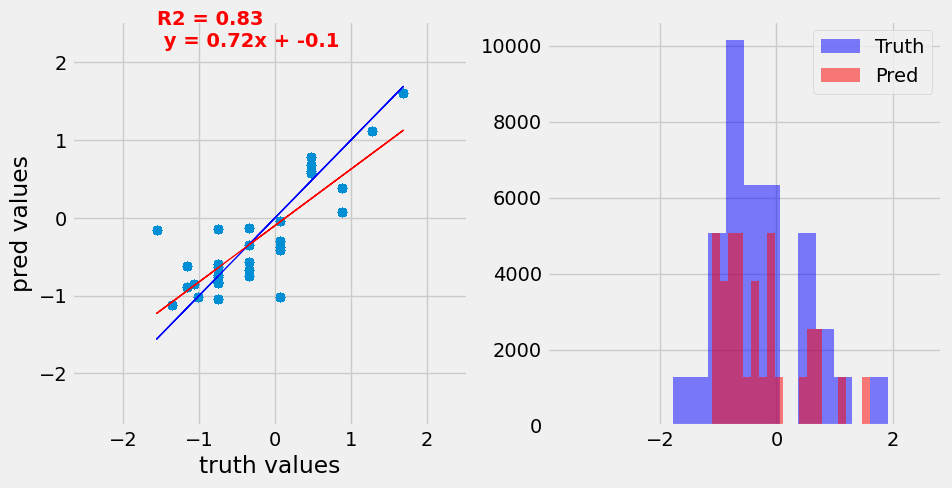

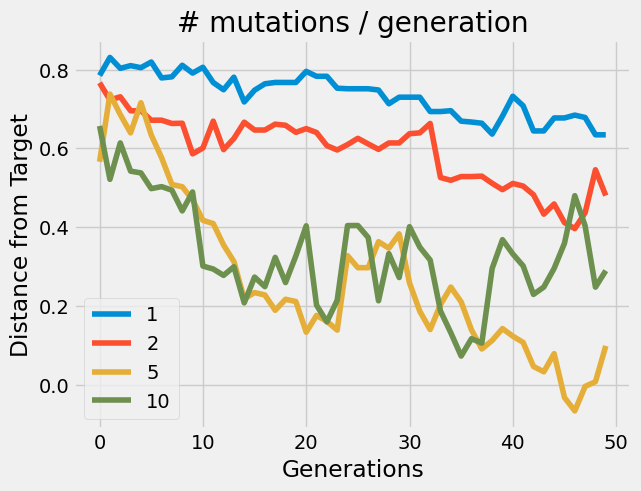

We can see how the genetic algorithm performs with varying numbers of mutations(just one parameter of the algorithm). We can see that the algorithm enables us to design promoter sequences effectively.

The genetic algorithm performs differently depending on the parameter of mutations per generation. The initial expression value was 0.8 and the target values was -0.5 (normalized values). The algorithm was able to find a solution to mutate/evolve the input promoter

Improvements

Both the CNN and genetic algorithm are designed as baselines to be improved upon. Here are some ways each could be improved.

The CNN is currently in a basic state.

It’s a shallow network; we only have 1 convolution and pooling layer. Typically the advantage of convolutions emerges with many of these layers. So we could stack 3-5 of these to condense the sequence representation into a single value or just a handful. This would mean we pass a fraction of the values to the input layers at the end compared to our baseline model.

Additionally, we could add skip connections from the first convolutional layer to the final one; this perserves information present at the beginning which may be lost due poor filters or the pooling layers.

Kernel sizes; could be varied. This is important because it determines how many base pairs are considered at a given time, longer kernels may learn different features than shorter ones.

The genetic algorithm has many more improvements which can be made.

The fitness function ; doesn’t factor in the number of mutations from the original sequence; perhaps we only want to perform 3 SNP mutations. This has relevance in the real world due to political regulations which may constrain the number of ‘novel’ mutations which may be performed in an individual.

More mutations; could be added like inversions, deletions, additions which affect multiple base pairs at a time. This quickly adds to the diversity of the population.

Genetic Flow; could be simulated with multiple genetic algorithms running in parallel. By the nature of evolution they would like evolve in seperate manners. Individuals from each population (you can think of them as islands of individuals) could be swapped each generation.

Breeding; with other individuals present in the population to simulate crossing over between distinct branches of the population. This would enable the combination of multiple mutations of benefit must faster from individuals with high scores.

Summary

We can see how effective CNN’s and Genetic algorithms are a accomplishing the task of learning patterns in promoter sequences then optimizing them for a target expression value. These are two tools which, while effective, are not exactly cutting edge, however, assist in the understanding of how other machine learning and optimization models work.

The CNN was originally developed for images and has been subsequently used for text based tasks, especially in genetics. While the do consider spatial elements, they are not particularly good at preserving or utilizing them inside the model. Recurrent Neural Networks like the Long-Short Term Memory and Gated Recurrent Unit networks are more popular for text since they recognize patterns sequentially over one character or more at a time. Even more recent, is the application of transformers which are notable for being attention based; learning to focus on particular characters over the whole sequence.

Genetic algorithms have not been popular for a while, partly in due to the resurgence of neural networks which were only recently viable due to improvements of computational power, and key components improvements to components like stochastic gradient descent. A good example of this was the use of gradient ascent by Kotokpa and Smolke, who used this approach to develop new promoters with their CNN.

During the explorations of CNNs and genetic algorithms, I developed a new library for dealing with genetic data and deep learning models. All the code for this article has been deposited on github at https://www.github.com/cjgo/bionlp. If you are a student, you can work on implementing the aforementioned improvements. In the future, further development of this library will extend to various NLP models like transformers for working with DNA and Protein data.